“Antisemitism is in the DNA of Austrians,” says Olga Neuwirth. “Maybe it skipped a generation but now it’s back – along with hatred for refugees.” We are speaking in a hotel bar in Vienna ahead of the premiere of the Austrian composer’s score for an extraordinary silent movie from 1924 called The City Without Jews, and she is worried about how it will go down with the locals.

After all, she says, it’s not long ago that anti-Muslim protesters interrupted a performance at Vienna University of a play about refugees, storming the stage to unfurl a banner reading “multi-culturalism kills”.

Similar rightwing protests greeted screenings of Die Stadt ohne Juden (The City Without Jews) in 1924. Fascists threw stink bombs into cinemas, and in the city of Linz the film was banned.

Neuwirth’s music for the film has its UK premiere on 15 November at London’s Barbican Centre. She doesn’t know what to expect from British audiences, though isn’t anticipating stink bombs or banners. The film is being screened as part of the Barbican’s Art of Change season, which aims to explore how artists can represent and change the political landscape. “I want to do that for sure,” she laughs. “Trump and other rightwing demagogues show how language and rhetoric can be used to whip up hatred. This film got there before them. Hopefully it can help us think about where we’re going wrong.”

The film – thought lost but discovered in 2015 in a Parisian flea market and digitally restored thanks to a crowdfunding campaign – is a dramatisation of a bitter satire of antisemitism by a Jewish journalist called Hugo Bettauer. His 1922 novel is set in a contemporary Vienna humbled by defeat in the first world war and collapse of the Habsburg Empire. Inflation and unemployment are soaring and politicians are looking for a scapegoat. “The people,” the chancellor announces in the film adaptation, “demand the expulsion of all Jews.” And Vienna’s 200,000 Jews are forced to emigrate.

“One of the most powerful scenes for me is of the Jews walking out of Vienna as it’s gathering dusk,” says Neuwirth, who is herself Jewish. “When I was writing the score, I had to suppress my rage or else the film would have had music which is just an expression of my fury.” Another unbearable scene shows trains loaded with Jews heading off to other European capitals and to Palestine. It’s hard not to see these trains as prefiguring other trains that would, within 20 years, take millions of Jews to Nazi death camps.

For all that Die Stadt ohne Juden is 94 years old, its revival in 2018 is resonant in an age of rising racist populism. “The parallels are plain: toxic language is begetting hatred, now as then,” says Neuwirth. “The chancellor is not initially an antisemite, but when he sees how well hating Jews plays with the masses, he seizes on the plan to throw them out.” She recalls what Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi said of the Holocaust: “If it happened once, it can happen again.”

But Bettauer’s novel imagines that ultimately the Austrian state invites the exiled Jews to return. Vienna struggles without them: “The idea is that only mediocrities remain,” explains Neuwirth.

It’s an understandable point. One thing that made interwar Vienna other than mediocre was its Jews. Composers including Arnold Schoenberg, writers such as Arthur Schnitzler and Stefan Zweig, made the Austrian capital intellectually and artistically exciting, while the city was also renowned for its Jewish scientists and doctors, including Sigmund Freud.

What Austria lost was made plain last weekend when the Nobel laureate Eric Kandel spoke in Vienna at the opening of the Austrian History Museum: this Jewish neuroscientist was forced to leave Austria in 1938 for the US, and so his pioneering work contributed to the glory of American rather than Austrian science. Since the Second World War, the number of Jews in Germany, Austria and the rest of Europe has fallen steadily - from 9.4 million in 1939 to 1.4 million in 2010 as Kandel pointed out.

One of those 1.4 million is Neuwirth. “The Austrian state never invited exiled Jews to return after the second world war. The German state did so, but not mine,” she says. Her own family survived the Nazi era by denying their Jewish identity. “I come from a long line of lawyers, and one of my ancestors who believed in the rule of law and didn’t want to be defined as a Jew asked the Emperor if he could officially define his family as having no religion. My grandfather similarly believed in the rule of law rather than religious law. Our family hid its identity.” Would you have done the same? “I can’t judge what my grandfather did to survive. But I cannot live like that – I cannot hide who I am.”

Unlike Bettauer’s book, the film ends with a formerly antisemitic councillor awaking from a drunken stupor in a Vienna tavern. “Thank God that stupid dream is over,” he says. “We are all just people and we don’t want hate – we want life – we want to live together in peace.’”

“Ugh!” says Neuwirth. “It’s all very well to say that. Of course we should want that. But the point of the novel was to show that we can so easily hate and not live in peace. That gets lost in the film.”

The movie also included farcical elements such as our hero, Jewish artist Leo Strokosh, returning to Vienna during the ban on Jews, sporting a ludicrous moustache and posing as a French painter to win back his Aryan girlfriend. Bettauer, not surprisingly, disowned the film.

But its notoriety, as well as the book’s success, made him into a target for antisemites, and, a year after the film’s release, Bettauer was murdered by a Nazi called Otto Rothstock. In another gruesome twist, the film’s director, HK Breslauer, joined the Nazi party in 1940. “Vile, I know,” says Neuwirth. “But he did so because he knew it was the way to get work.”

How does Neuwirth feel to have written a score for a film she regards as a cop-out? “Conflicted!” She initially turned the project down because she was writing her long-cherished operatic adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando. “Then the head of the Vienna Biennale stopped me in the street and told me I must do it.” Because you’re an Austrian Jewish composer? “That, but also because he said I was one of the ‘Other Austrians’ – those few artists and intellectuals who have a critical stance on what is going on.”

And what is going on? “Austria is always the trailblazer for hatred. There was Jörg Haider [the controversial Austrian far-right politician], long before the new wave of populist haters such as Trump.”

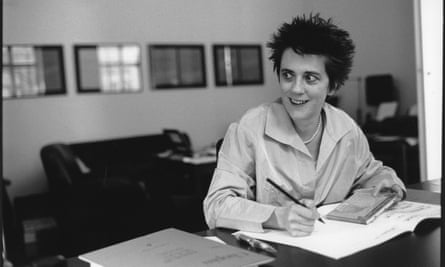

Neuwirth was born in 1968 in Graz, a trumpet-playing prodigy as a teenager until a jaw injury put paid to that ambition. She studied fine art and film in San Francisco and music in Paris. Today she has written more than 100 works including orchestral pieces, chamber works, music theatre pieces, as well as unclassifiable multimedia hybrids of film, theatre, and performance art.

To get a sense of the range of her work, consider some of the premieres in recent months. In August, the day after her 50th birthday, saw the Proms premiere of her Aello – ballet mécanomorphe. In September, fumbling & tumbling for solo trumpet premiered in Munich, and a new production of her acclaimed 2003 operatic adaptation of the David Lynch film The Lost Highway opened in Frankfurt.

Orlando premieres at the Vienna Opera House next year. “I read the book aged 14 and loved it. But in the novel the action ends in 1928. I take it up to now, speeding up the action in the music, getting more and more wild as we reach today. And, in the book, the child Orlando has is imagined as a boy, I imagine it as a mix, gender fluid.” That seems fitting, given Orlando’s status as English language’s first trans novel.

What did teenage Olga love about Orlando? “It’s about female creativity and the freedom to speak out. It still resonates.”

Neuwirth takes that freedom to speak out seriously. Is she worried about how her outspokenness and political engagement will provoke enemies? “Worried maybe. Silenced no.” She quotes the great German Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt: “You have no right to obey.” “That’s great isn’t it?” Perhaps the corollary is sometimes you have a responsibility to disobey? “That’s what I think artists are sometimes for, to say no to the rise of hatred.”

Die Stadt ohne Juden is at the Barbican, London, on 15 November.